Overview

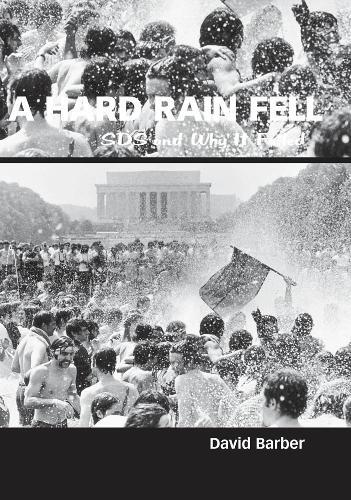

By the spring of 1969, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) had reached its zenith as the largest, most radical movement of white youth in American history-a genuine New Left. Yet less than a year later, SDS splintered into warring factions and ceased to exist. SDS's development and its dissolution grew directly out of the organization's relations with the black freedom movement, the movement against the Vietnam War, and the newly emerging struggle for women's liberation. For a moment, young white people could comprehend their world in new and revolutionary ways. But New Leftists did not respond as a tabula rasa. On the contrary, these young people's consciousnesses, their culture, their identities had arisen out of a history which, for hundreds of years, had privileged white over black, men over women, and America over the rest of the world. Such a history could not help but distort the vision and practice of these activists, good intentions notwithstanding. A Hard Rain Fell: SDS and Why It Failed traces these activists in their relation to other movements and demonstrates that the New Left\'s dissolution flowed directly from SDS's failure to break with traditional American notions of race, sex, and empire.

Full Product Details

Author: David Barber

Publisher: University Press of Mississippi

Imprint: University Press of Mississippi

Dimensions:

Width: 15.20cm

, Height: 1.70cm

, Length: 22.80cm

Weight: 0.333kg

ISBN: 9781604738551

ISBN 10: 1604738553

Pages: 300

Publication Date: 30 June 2010

Audience:

Professional and scholarly

,

Professional & Vocational

Format: Paperback

Publisher's Status: Active

Availability: Manufactured on demand

We will order this item for you from a manufactured on demand supplier.

Reviews

With his book title David Barber makes clear for his readers what this text's purpose is: to explain the failure of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). With forty years to reflect on the history of this organization, Barber has clearly identified the mistakes of the past: a failure on the part of young male activists to comprehend the concept of white skin privilege and a refusal to follow the advice of African American activists, especially those in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP), who urged them to go back to their white communities and combat racism there. They also failed to acknowledge the intellectual leadership role that blacks had played in the past (W. E. B. Du Bois and Malcolm X) and should rightfully assume in the black liberation movement. Furthermore, men in SDS ignored the contributions of women in the face of a growing feminist movement, thereby driving out some of their most dedicated members. They also did not listen to Vietnam war protesters who urged them to build a broadly based antiwar constituency in the United States. Instead, many leaders in SDS succumbed to a macho, self-indulgent and, in the end, self-destructive vision of a revolutionary movement centered around white male leadership. In order to make his argument, Barber presents an extremely detailed analysis of all the permutations of SDS: from its origins in the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, when it developed as an ally of urban poor people and an initial leader in the antiwar movement, to its fractious end with bombings and confusion in the late 1960s. Along the way he explains the break with the more conservative Progressive Labor Party (PL), as well as the differences among the Revolutionary Youth Movement I (the Weathermen) and Revolutionary Youth Movement II factions. He also provides a nuanced account of the origins of the women's liberation movement that breaks down the divisions between the women who tried to stay within the ranks of the New Left (the a politicosa ?) and the radical feminists who, after being scorned and booed at SDS meetings, left and formed their own political groups. The main theme of the author's criticism here is that the young, white, male activists in SDS did not see that they were continuing the errors of traditional American culture by assuming that, because of their white skin, they were necessarily the leaders of a progressive student movement. He argues that a the New Left failed not because it radically separated itself from America's mainstream, the claim of a number of important historians of the period. Rather, it failed because it came to mirror that mainstream, and in mirroring .a American racial attitudes, it ceased to represent a Lefta ? (p. 8). In the end, SDS came to be dominated by the Weatherman and Weatherwoman factions that wanted to a out-machoa ? the white working class by brawling with the police and blowing up buildings. As a result, when huge numbers of Americans took to the streets to protest the war in 1969 and 1970, SDS was nowhere to be found. They had abdicated leadership in the most important antiwar effort of that decade. In the end, leaders in SDS were guilty of refusing to work at community organizing, building alliances, and resisting imperialism. What then are we to make of all of this? Barber builds a solid case for the argument that many leaders in SDS were blind to their privileges as white men, and that they did not acknowledge the contributions of both African Americans and women. And yet I wonder if we can so clearly place blame on all those who were part of that time and that culture. I am reminded of Alice Echols's conclusion in Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin (1999): a Nevertheless, mistakes were surely made, not the least being the assumption that personal and cultural transformation could be easily achieveda a matter of breaking off and breaking through. It was an assumption that blinded us to how deeply marked we all were by the conventions and expectations of the mainstream, no matter how a countera we proclaimed ourselvesa ? (p. 305). The mistakes of activists in SDS were those of the culture that they came from, but those errorsa and the ways in which women and African Americans reacted to thema paved the way for a more inclusive and more pragmatic progressive movement. Calls for revolution have been replaced by continued efforts for international peace and more-equitable distribution of opportunities for people of color and women, and there is obviously much more to be done. However, we do learn from the past, and Barber has served us well in making that point. The American Historical Review

<p>The main theme of the author's criticism here is that the young, white, male activists in SDS did not see that they were continuing the errors of traditional American culture by assuming that, because of their white skin, they were necessarily the leaders of a progressive student movement. He argues that the New Left failed not because it radically separated itself from America's mainstream, the claim of a number of important historians of the period. Rather, it failed because it came to mirror that mainstream, and in mirroring American racial attitudes, it ceased to represent a Left. In the end, SDS came to be dominated by the Weatherman and Weatherwoman factions that wanted to out-macho the white working class by brawling with the police and blowing up buildings. As a result, when huge numbers of Americans took to the streets to protest the war in 1969 and 1970, SDS was nowhere to be found. They had abdicated leadership in the most important antiwar effort of that decade. In the

The main theme of the author s criticism here is that the young, white, male activists in SDS did not see that they were continuing the errors of traditional American culture by assuming that, because of their white skin, they were necessarily the leaders of a progressive student movement. He argues that the New Left failed not because it radically separated itself from America s mainstream, the claim of a number of important historians of the period. Rather, it failed because it came to mirror that mainstream, and in mirroring American racial attitudes, it ceased to represent a Left. In the end, SDS came to be dominated by the Weatherman and Weatherwoman factions that wanted to out-macho the white working class by brawling with the police and blowing up buildings. As a result, when huge numbers of Americans took to the streets to protest the war in 1969 and 1970, SDS was nowhere to be found. They had abdicated leadership in the most important anti-war effort of that decade. In the end, leaders in SDS were guilty of refusing to work at community organizing, building alliances, and resisting imperialism. The American Historical Review

<p>With his book title David Barber makes clear for his readers what this text's purpose is: to explain the failure of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). With forty years to reflect on the history of this organization, Barber has clearly identified the mistakes of the past: a failure on the part of young male activists to comprehend the concept of white skin privilege and a refusal to follow the advice of African American activists, especially those in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panther Party (BPP), who urged them to go back to their white communities and combat racism there. They also failed to acknowledge the intellectual leadership role that blacks had played in the past (W. E. B. Du Bois and Malcolm X) and should rightfully assume in the black liberation movement. Furthermore, men in SDS ignored the contributions of women in the face of a growing feminist movement, thereby driving out some of their most dedicated members. They also did not listen to Vietnam war protesters who urged them to build a broadly based antiwar constituency in the United States. Instead, many leaders in SDS succumbed to a macho, self-indulgent and, in the end, self-destructive vision of a revolutionary movement centered around white male leadership.<p> <p><br>In order to make his argument, Barber presents an extremely detailed analysis of all the permutations of SDS: from its origins in the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, when it developed as an ally of urban poor people and an initial leader in the antiwar movement, to its fractious end with bombings and confusion in the late 1960s. Along the way he explains the break with the more conservative Progressive Labor Party (PL), as well as the differences among the Revolutionary Youth Movement I (the Weathermen) and Revolutionary Youth Movement II factions. He also provides a nuanced account of the origins of the women's liberation movement that breaks down the divisions between

Author Information

David Barber is assistant professor of history at the University of Tennessee at Martin. His work has appeared in Journal of Social History, Left History, and Race Traitor.